Relatively few valley residents today are aware that people of Japanese ancestry played a significant role in the early history of West Covina. During the first two decades of the 20th century, dozens of farmers emigrated from Japan to settle here, owning and working the land, raising families and becoming productive members of the local community.

And what a community it was! Early West Covina was a remarkable assemblage of nationalities. No previous author has stated this specifically, but unlike the parent city,1 there was no racial separation to speak of in pre-war West Covina. Americans, Europeans, and first-generation immigrants from Japan (termed "Issei") all lived, farmed and participated in society with full freedom of association. There's perhaps no better visual evidence of this societal integration than this photo of Grades 1-3 at West Covina School in 1938. Look at all those happy faces!

Teacher Frances Maxson Sanchez (1900-1999) was the daughter of West Covina's first mayor, Benjamin Franklin Maxson, Jr., and her husband, Juan C. Sanchez, was a great-grandson of founding pioneer John Rowland.2

The grownups also mingled socially. Newspaper accounts describe many inclusive community meetings and celebrations, especially what became an annual Japan-themed dinner hosted by the West Covina Parent-Teacher Association. Year after year, front page articles in the Covina Argus reported on these much-anticipated festivities that were attended by as many as 200 locals,3 which was quite a crowd in those days.

The number of Japanese households in pre-war West Covina was substantial. In preparation for this article, I examined official U.S. Census enumeration records and found that, in 1940, people of Japanese ancestry comprised 17.2% of all residents in the greater West Covina area, and 11.1% within the city limits proper. (Hispanics were a distant third at 2.9% of all city residents in 1940.)4 Even twenty years previous to that, the percentage of Japanese in the area stood at 14.4%.5

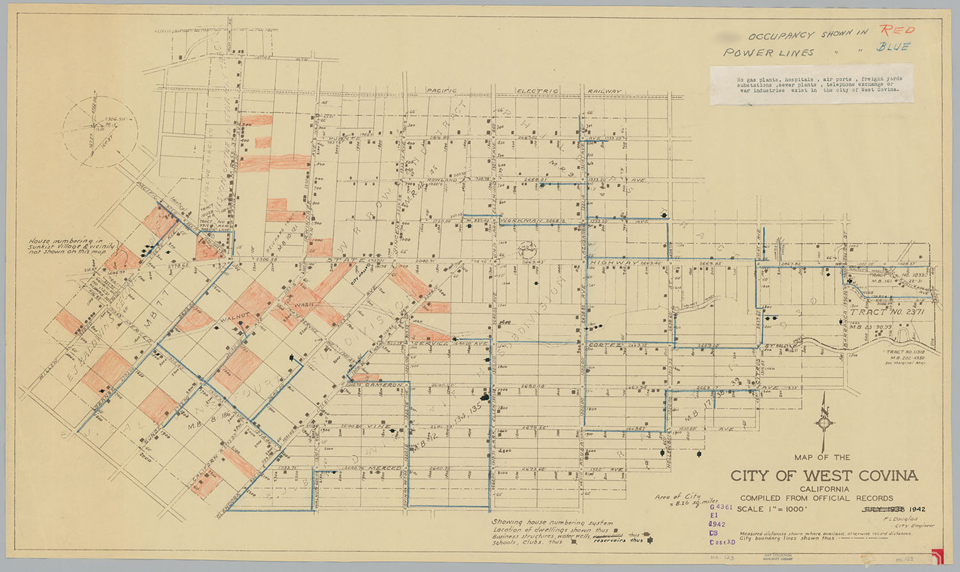

Also, judging by this map, the Issei families of West Covina owned a commensurate proportion of the section's farmland.

Wartime map showing Japanese occupancy in West Covina, indicated in red. Compare with a similar map of the greater Covina area; very little red there.

Source: Earl Warren Pre-evacuation Maps, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The most prominent early Japanese family in West Covina was headed by the town's first Issei settler, Machida Eijiro. In the 19-teens, Mr. Machida founded the Orange Avenue Japanese Association, forerunner of today's East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center. His son, Eiichi (anglicized as "Eachi"), attended West Covina School and Covina Union High School. At the latter, Eachi was a popular student, football quarterback, baseball letterman,6,7,8 and in 1931 he became the school's first Nisei graduate.9 Both elder and junior Machida received numerous favorable mentions in the Argus and Citizen during the Thirties.

Then war came, and turned the world upside down. Following President Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 in February, 1942, all people of Japanese ancestry were ordered relocated and detained for the duration of hostilities. The Machidas were uprooted from their home soil and interned at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center10 in far-northern California.

A few of the wrongly-displaced Issei and Nisei returned to West Covina after the war, but of course things were never the same, especially when suburban growth exploded and all the former farmlands were developed. West Covina's Japanese heritage has not been forgotten, however; now lovingly preserved by Mr. Machida's East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center, and celebrated during the ESGVJCC's annual Cherry Blossom Festival.

As a further commemoration, I submit the following Honor Roll of all the Issei immigrant fathers of West Covina in 1940. For everything positive they contributed to the community during its pioneering first four decades, and all they endured thereafter, they rightfully deserve to have their names written into history at long last.

Fujimoto Riichi

Hamachi Shotaro

Haremoto Mitsu

Hashimoto Hiroshi*

Hatakiyama Kimeo*

Higa Jiro

Hirashiki A.*

Izumi S.*

Kadota Jusaku

Kajiki Niichi

Kanibara Tsurukiehi

Kawakami Takemea

Kawata Yoshi

Kinoshita Sanji

Kobayahshi R.*

Kosha Takichi

Machida Eijiro*

Makashima Tahichi

Otto Maye

Mayeda Motonori

Mikawa Kasaku

Miyahara Hiroshi*

Miyakaiwa Takei

Motoharu Sumida

Murikami Seiichi

Nagasawa Toru*

Nakada T.*

Nakamuro E.*

Namekata Benzo*

Nishiyama Uhichi

Nozaki B.*

Okada Aiichi

Okada Kazui

Tom Okada

Okano Take

Oshiro Kanko*

Oshiro Seyei

Sakata Jukichi

Sakata Zuza

Sakatani Takami

Sawada Kanshiro*

Sera G.*

Shimomoto Mosomichi

Shiraki Sue*

Sogioka S.*

Suzuki Takeji

Tamaki Kei*

Tekara Tee*

Terada Shoichi

Tokeshi Dokei

Tokeshi Doshu

Tokeshi Mitsu

Toyoma Monitaro*

Tsuroda Yohshi*

Wakino Tsuruichi

Yaburita Hikaroku

Yamada Kametaro

Yamamoto G.*

George Yanaoka*

Yokoe Kinsaburo

Yoshimura Seijiro

*Resided within the city limits of West Covina in 1940.4

––This article is dedicated to our old family friends–Leo, Vi and Mike Okura–and also to the memory of my father–Ed Shannon–who instilled in me a lifelong appreciation of the Japanese people and their culture––

References:

1 Pflueger, D. H. 1964. Covina: Sunflowers, Citrus, Subdivisions. Castle Press, Pasadena, California, 372pp.

2 Personal communication with Reed Maxson.

3 Covina Argus, January 19, 1934, p.10.

4 United States Census, 1940.

5 United States Census, 1920.

6 Covina Citizen, August 4, 1933, p.1.

7 Covina Argus, November 7, 1930, p.2.

8 Covina Argus, June 6, 1930, p.1.

9 Covina Citizen, June 11, 1931, p.1.

10 Sorted By Name.com.

1 comment:

Thank you for this post. I wasn't aware of the extent of Issei in West Covina.

One cannot read your posts without learning something new - or previously unknown.

Post a Comment

To post a comment, you must login to this page with the Google Chrome web browser. That is the only way that works now.