Everybody who grew up in Covina is familiar with the name Hollenbeck, but few know the historical figure's actual connection to the city. Turns out Covina as we know it wouldn't have existed without John Edward Hollenbeck and his business dealings and personal associations in Central America from 1849-1876.

J. Edward Hollenbeck (1829-1885). Source: An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County, California, 1889, at archive.org.

Hollenbeck engaged in several commercial enterprises during his 27 years spent mostly in Nicaragua, but the most salient with regard to Covina is the period after the American Civil War when he was an export agent for the Royal Mail.1 Hollenbeck oversaw international transactions of a wide variety of trade goods, and it was likely then that he crossed paths with the wealthy coffee-growing family of José de Jesús Badilla of Heredia, Costa Rica. José Badilla died in 1875,2 but by way of inheritance, and Hollenbeck, it would be his sons who ended up becoming the first settlers on the land which would one day become Covina.

In his notable history of Covina,3 Donald Pflueger wrote that it was Hollenbeck's suggestion that the Badillos emigrate to California to grow coffee. [N.b., for the purpose of this article, the two spellings (Badilla/Badillo) are considered to be interchangeable and of equally valid historicity.] Quoting:

The Costa Rica Ranch had been acquired by the Badillo brothers when they came into the valley at the instigation of John E. Hollenbeck, a prominent resident of Los Angeles who owned a magnificent home in Boyle Heights. Mr. Hollenbeck had spent many years in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, and while in Costa Rica he became acquainted with Julián and Antonio Badillo, well-to-do owners of coffee plantations. Although Mr. Hollenbeck did not understand the cultivation of coffee, he conceived the idea of establishing a coffee plantation in the San Gabriel Valley and approached the Badillo brothers on the matter.3

This has always been the accepted story, however, the deeper I have delved into the lives of Hollenbeck and the Badillas–examining in particular the actual historical sequence of events–the less likely it seems this was the American's idea. It's problematic to Pflueger's account that Hollenbeck didn't come to live in Los Angeles until March, 1876,1,4 only two months before the Badillos first arrived there.5 It seems improbable to me that a family that had been growing coffee successfully in Costa Rica for generations would completely uproot itself and move to a foreign country based solely upon the speculation of one man who had no experience growing their crop, and who up to that point had never himself lived in California.

What makes more logical sense is that the Badillas came up with the idea of moving to the United States themselves, and subsequently sought out the locally famous American expatriate, Hollenbeck, to help facilitate their plan. Apparently, he was known to be a ready ally to people who wanted to improve their lot in life. In an old biography, Hollenbeck was described as being noted for his "...large-hearted generosity, always assisting every worthy enterprise, and ever willing to help those who showed a disposition to help themselves."1 For the Badillas, J. E. Hollenbeck would seem to have been the right man in the right place at the right time to help them relocate to America.

Although I admit the above scenario is speculation, I have found indirect support for it in a memoir written by Covina pioneer Clara Eckles (1874-1966), who knew the (Antonio) Badillo family personally when she was a girl. Miss Eckles wrote that Mr. Badillo himself explained why they came to this country: they wanted "...a coffee plantation, yielding enough coffee for the whole United States!"6 Even Hollenbeck couldn't credibly pitch an idea that grandly ambitious. A big dream like that would also help explain why the family bought such a huge area of land, and were willing to pay such a high price for it.

Detail of 1877 map of Los Angeles County showing the original boundaries of the 5,563-acre Badilla Tract (yellow), and the 2,100-acre partition (olive) which ultimately became Covina. Source: Library of Congress

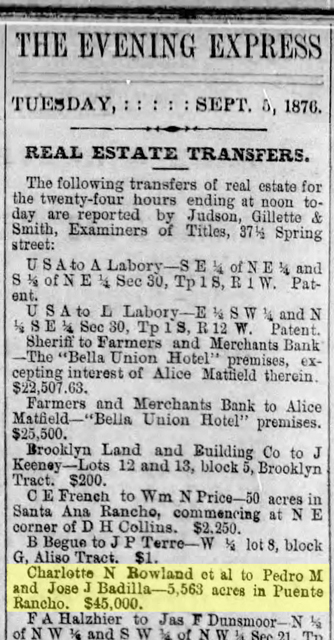

Once they made their plans to come to California, the Badillas apparently wasted no time. The first newspaper articles I found mentioning them here was a ship manifest published in the May 18, 1876 edition of the Los Angeles Daily Star,5 and the registry of the Lafayette Hotel in the Los Angeles Evening Express on May 20, 1876.7 The two eldest brothers subsequently bought their land from John Rowland's widow Charlotte M. Rowland, her son Albert Rowland and daughter Victoria Rowland on September 2, 1876.8,9

Legal notice for the purchase of the Badilla Tract in Rancho La Puente, Los Angeles Evening Express, Sept. 5, 1876.8

With the ink barely dry on their deed, the Badillas got straight to work building their houses and growing coffee,3 and were already producing beans the following January.10

![[We were shown this afternoon, by Mr. Sotello,] a very fine specimen of coffee-berry, raised on the Puente Rancho by the Badillo Brothers. [...] They planted about 1,000 coffee trees, 500 of which have thriven.](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/500_badillo_coffee_plants_thrive_011377_covinapast.jpg)

On page 24 of his history, Pflueger continues telling the now firmly-entrenched legend that the Badillos tried and failed to grow coffee due to the arid climate of the San Gabriel Valley.3 Newspaper articles from the time, however, tell a slightly different story: although climate was a negative factor, the Badillo Brothers did successfully cultivate the plants, it was just not economically sustainable to grow or market commercial quantities of the product.11

![[Title: The Cultivation of Coffee.] [...] the Badillo brothers, [...] purchased land on the Puente ranch, and with ample means tried the experiment. By great care and nursing the tree has been made to grow and to bear the berry; but the success has not been proportioned to the labor and expense attending the experiment.](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/badillo_coffee_successful_but_not_economical_030578_covinapast.jpg)

Santa Barbara Daily Press, March 5, 1878.11

Pflueger then goes on to say that the Badillos also tried and failed to grow coffee the following year,3 but again, newspapers of the day paint a different picture: the Badillos were notably successful growing wheat in 1878, and printed glowing accounts of their achievement.12,13,14,15,16 (Pflueger, on the other hand, never mentions wheat in connection with the Badillos at all; a significant historical omission, as the articles below clearly attest.)

Santa Barbara Daily Press, April 18, 1878.12

![In the Azusa, the Costa Ricans who sowed Egyptian wheat will reap excellent crops. This staple don't rust and we hope to see it introduced quite extensively hereabouts. [...] We have never seen finer wheat than the Egyptian staple in which Mr. Badillo has sown a thousand acres in the Azusa. It is absolutely free from 'rust' and is exactly adapted to our climate.](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/badillo_fine_wheat_061578_covinapast.jpg)

Los Angeles Herald, June 15, 1878.13

La Crónica, June 19, 1878.14 Click here for translation.

![[...] The Costa Ricans who, like Señor Badilla, have been cultivating wheat extensively in the Asuza [sic] have, without an exception, superb crops. This is because these sensible people were careful to search out and sow a wheat suited to the climate of Southern California.](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/badillas_wheat_suited_to_climate_072178_covinapast.jpg)

Los Angeles Herald, July 21, 1878.15

![Wiley & Morehouse are taking in store daily about a thousand sacks of Egyptian wheat from the ranch of Badillo Brothers in the Puente. This wheat is never troubled with rust and yields enormously. The crop will be sold for seed [...]](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/1000_sacks_of_badillo_wheat_a_day_083178_covinapast.jpg)

San Luis Obispo Tribune, August 31, 1878.16

It should be obvious by now that the apocryphal stories about the Badillas having "failed" are just plain wrong. The brothers were, in actuality, remarkably adept agriculturists, growing crops under conditions that apparently few others could.

So, given these successes, why, then, did these advertisements start appearing in the Los Angeles Herald from December 8, 1878–January 17, 1879?17

Ad in Los Angeles Herald, December 8, 1878.17 This is the same land that became the Phillps Tract where Covina would be founded in 1885.

Only four months before, the Badillas had figuratively struck gold with their famous crop of Egyptian wheat, and yet now, they're selling their prime wheat-growing land? On the surface, this doesn't make sense. Why would they do that?

The accepted story as told by Pflueger is that Julián Badillo became discouraged after his second year failing to grow coffee and moved his family away, but Antonio stayed, tried growing other crops, went into debt and borrowed "large sums of money" from Hollenbeck's bank. Unable to pay back the loan, the bank foreclosed on Antonio, Hollenbeck bought the land at the foreclosure sale, and gave 100 acres gratis to Antonio so that he could continue living and farming on his former land.3

We now know, though, that in 1878, the Badillas harvested one-thousand acres of wheat during a season in which a significant portion of the wheat crop of southern California was destroyed by a rust blight. "A thousand sacks of Egyptian wheat" a day were coming in from the Badillo Ranch, and so valuable that it was all sold for seed instead of being milled for flour. They must have made a small fortune that year! So why would any member of the family have to borrow money, let alone put their land up for sale? Something just doesn't add up here.

The ad above is worth scrutinizing, because it contains important historical information. First of all, notice that Julián Badilla is not mentioned. He was one of the legal co-owners of the land, so logically he should have been named as a contact, but he was not. Why? I take this as circumstantial evidence that Julián had already left California for Mexico18 by the winter of 1878-1879, when this ad first appeared. Instead, the contacts are Pedro (Antonio)19 Badilla and Rev. P(edro) M(aría) Badilla.20 (Pflueger doesn't mention co-owner Pedro María at all, which is another major factual omission. We also discover from this ad that Pbro. Badilla was apparently an assistant to the Bishop of Los Angeles, not a farmer working the family's Azusa Valley ranch.) It's also worth pointing out here that because Antonio was not one of the land owners at that time,8,9 he likely would have found it impossible to borrow "large sums of money" from any bank, as he did not own any real property that he could have put up as collateral.

Now consider the published legal notice for the foreclosure action against the Badillas, which ran in the Los Angeles Herald from June 5-July 2, 1879.21 Note that the only Badillas named as defendants are Pedro María and José Julián, not Antonio as Pflueger stated, and that J. E. Hollenbeck is pursuing this action as an individual, not as an officer or representative of his bank. What this implies is that P. M. and J. J. Badilla borrowed the undisclosed sum of money directly from Hollenbeck. He was foreclosing on a secured personal loan.

![Mortgage Sale. No. 5,091. J. E. Hollenbeck, Plaintiff, vs. Pedro Maria Badilla, Jose Julian Badilla, [et al.] Defendants. Seventeenth District Court. UNDER AND BY VIRTUE OF A decree of foreclosure and order of sale entered in the District Court of the Seventeenth Judicial District of the State of California, in and for the county of Los Angeles on the 3d day of June, A.D. 1879, in the above entitled action, and in favor of J. E. Hollenbeck, plaintiff [...] Public notice is hereby given that on FRIDAY, THE 27TH DAY OF JUNE, A.D. 1879, At 12 o'clock M., of said day, I will proceed to sell [...] at public auction [...] all the above described real estate. [sgd.] H. M. MITCHELL, Sheriff. [...]](https://otters.net/img/covinapast/hollenbeck_v_badilla_et_al_foreclosure_sale_notice_061079_covinapast.jpg)

Los Angeles Herald, June 5, 1879.21

It also seems reasonable to assume that whatever sum the two elder Badilla brothers borrowed must have been long past due by the time Hollenbeck initiated his foreclosure action in June, 1879. Pflueger stated that Antonio only borrowed money from Hollenbeck's bank after Julián left,3 but aside from the fact that Julián did leave, and Hollenbeck did subsequently acquire the land and gift Antonio 100 acres, we now know that not a single other detail of that account is historically correct. And far from being a debtor or a welsher, Antonio Badilla appears to have been a completely innocent party in this affair, which I think is further evidenced by Hollenbeck's altruistic generosity to Antonio after the unfortunate foreclosure process against his elder brothers was concluded.

At this point, two major questions remain unanswered. First, what happened to all the money that the Badillas must have gotten for their famously bountiful 1878 wheat crop? No one today can say for certain, but clearly, it didn't go to repay their debts; not even enough "good faith" money went to Hollenbeck to keep him from foreclosing. Second, if Julián Badilla was so successful growing wheat here in 1878, why didn't he simply stay and continue farming grain? Over time, he could have paid off whatever indebtedness he had, and later become quite well-to-do subdividing and selling land to settlers. It seems to me that had different decisions been made, there would today be a city named "Badilla" in the eastern San Gabriel Valley instead of one called "Covina." So exactly why Julián left California for Mexico18 will probably never be known. (Pbro. Pedro Badilla also left California for Mexico18 not long after Julián, and in February of 1886,22 Antonio sold his gifted land for $12,000 and moved most of his family back to Costa Rica. After 1880, Julián and Pbro. Badilla ended up spending the rest of their lives in Arizona Territory.18)

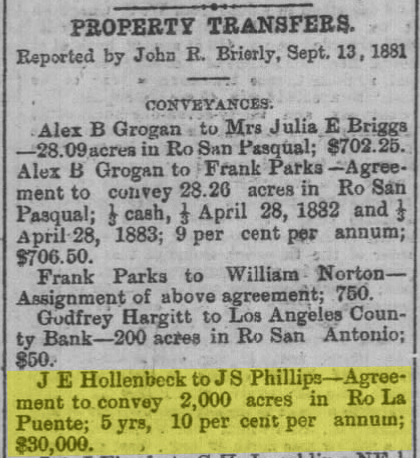

And what of Edward Hollenbeck: the man who catalyzed this whole series of events? He retained ownership of the former Badilla Tract, and on September 7, 1881, Hollenbeck agreed to convey a 2,000-acre portion of it to Joseph Swift Phillips for $30,000 with 5 years to pay in full23 (the same land described in the ad above) where the latter subsequently founded the town of Covina in winter 1884-1885. Unfortunately, Hollenbeck died of a stroke on September 2, 1885,24 so he never got to witness Covina prosper, or see the stately landmark fan palms that line the street that bears his name.

Legal notice of Hollenbeck and Phillips's conveyance agreement.23

And speaking of streets: the eternal question of why the street in Covina was named "Badillo" instead of the actual family name, Badilla. My theory is simple: "Badillo" was chosen because that was the name the brothers were best known by. Almost all of the contemporary newspaper articles about their agricultural pursuits used the "-o" spelling, and the Badilla families themselves even used it on occasion (evidenced by that ship manifest5–which would match the name that appeared on their travel documents). I've also seen their surname spelled "Badella" and "Badillio" in official records, which shouldn't be surprising considering spellings in general were more fluid in olden times.

In any case, which is more meaningful in the broader context: honoring and memorializing the Badillas by naming a main street after them, or which terminal vowel the surveyor used to spell that name on his map? The point is, the naming was a gift to the family, and as the old saying goes, it's the thought that counts. :-)

References:

1 Warner, J. J. 1889. An illustrated history of Los Angeles County, California. The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, 835pp.

2 Jose de Jesus Badilla Sanchez at FamilySearch.org

3 Pflueger, D. H. 1964. Covina: Sunflowers, Citrus, Subdivisions. Castle Press, Pasadena, California, 372pp.

4 Wilson, J. A. 1880. History of Los Angeles County, California. Thompson & West, Oakland, California, 192pp.

5 Los Angeles Daily Star, May 18, 1876, p.4.

6 Eckles, C. M. 1960. Memoirs of Clara Margaret Eckles (1874-1966), Karl W. Blackmun, ed. Unpublished manuscript, Covina Valley Historical Society, 16pp.

7 Los Angeles Evening Express, May 20, 1876, p.3.

8 Los Angeles Evening Express, September 5, 1876, p.3.

9 Pasadena Star News, November 26, 2011.

10 Los Angeles Evening Express, January 13, 1877, p.3.

11 Santa Barbara Daily Press, March 5, 1878, p.1.

12 Santa Barbara Daily Press, April 18, 1878, p.2.

13 Los Angeles Herald, June 15, 1878, p.2.

14 La Crónica, June 19, 1878, p.3.

15 Los Angeles Herald, July 21, 1878, p.2.

16 San Luis Obispo Tribune, August 31, 1878, p.2.

17 Los Angeles Herald, December 8, 1878, p.2–January 17, 1879, p.4.

18 Badilla Family History, Facebook page.

19 Pedro Antonio Badilla Bolaños at FamilySearch.org

20 Pbro. Pedro María Badilla Bolaños at FamilySearch.org

21 Los Angeles Herald, June 5, 1879, p.2-July 2, 1879, p.4.

22 Los Angeles Times, February 3, 1886, p.3.

23 Los Angeles Herald, September 14, 1881, p.3, and The Daily Commercial, September 15, 1881, p.3.

24 Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1885, p.1.

Grateful thanks to Randall Smith and Michael Schoenholtz for their helpful research, discussion and support.

No comments:

Post a Comment

To post a comment, you must login to this page with the Google Chrome web browser. That is the only way that works now.